Richard Wise, partner at Ryder Architecture, discusses the procurement and timescales involved in the school design process and the resulting impact on design quality

There is little disagreement that inadequate buildings have a negative impact on education outcomes and life opportunities for children. Poor spatial configurations, poor noise separation, overheating in summer or excessive cold in winter, poor air quality and daylight all impact personal performance whether in work settings, the home or places of learning.

By its nature the school estate will always have buildings that are at the end of their useful life, that no longer meet modern teaching requirements or support progressive learning methods. As such school improvement and replacement is a constant, requiring a rolling programme of investment to tackle failing stock and respond to changing demographics.

To manage programme delivery in the public sector there is a process in place orchestrated by the Department for Education (DfE) delivered through contractor frameworks; split by value, region and delivery model, such as off site manufactured solutions (MMC) or more traditional construction building solutions. The focus of the programme is to improve the building stock, but do the respective routes encourage and deliver well designed and well considered buildings, or are these outmoded requirements, which are more about aesthetics than function?

The MMC framework products are varied in quality and the more modular the product, the more temporary the aesthetic and I would suggest other than very few examples the product, however well thought through the assembly, is at its best a shinier version of what it replaces granted with significantly better environmental controls and envelope performance. It is still widely agreed that traditional delivery models produce a better product as there are greater degrees of flexibility to respond to the site and local environmental factors, and they have an inherent quality even if difficult to measure empirically.

Both routes require the input of design teams to navigate through the early design stages as well as the on site delivery. The influence of the designers varies but both routes are here to stay, and some of the results are very good.

Within the constraints we face can good become great?

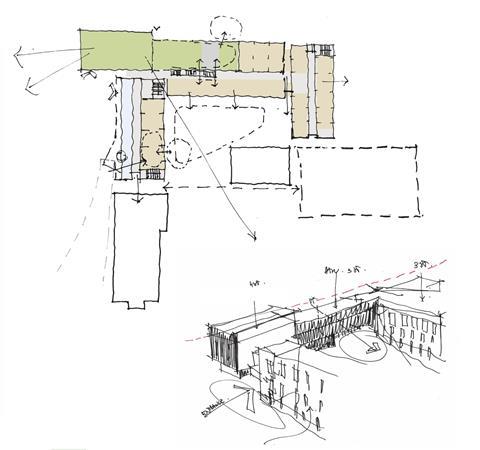

School design should not be idiosyncratic, but neither should it be a simple application of predetermined arrangements that do not suit circumstance, site, location and place. The 2011 Sebastian James report caused consternation in the design community, as it suggested an ‘out of the box’ approach. It was written on the premise that a predetermined school model can land on any site. The ‘Tesco principle’ is a well honed model of efficiency, a process overlayed with a psychology to encourage the shopper to make decisions that benefit the outlet not necessarily the shopper. As such, the Tesco experience in Kingston Park, Newcastle is exactly the same as the Tesco experience at Kingston upon Thames.

We would all agree there are some benefits to this, for example we know where things are in every store. There is however more to it than our convenience – there is the impact of product location, brand identification and a science behind the entire arrangement that encourages the customer to behave in a certain way. It is worth holding on to that thought. If buildings and their layouts influence our decision making, then surely, they can equally influence education outcomes?

Prescribed guidance

There is a language and grammar to all school design, particularly in the public sector. Other than the very odd exception, every school has similar if not identical components. The endeavours of the DfE collaborating with designers and constructors in leading this process should not be underestimated. The DfE provide a suite of documents, the facilities output specification (FOS), the school specific brief (SSB) and refer us to baseline designs. The FOS defines a working environment that is tightly prescribed to ensure that all the environmental failings listed above are not repeated. This is seen by some as too restrictive, stymying creativity in the design process and in consequence narrowing opportunity.

Within reason we all respect rules and would not baulk at designing to meet building regulation requirements. A working knowledge of the FOS is an efficient way of avoiding design issues that arise on every school project. So, the FOS needs to be respected and built upon rather than disregarded as an encumbrance. The FOS is an ‘in plain sight approach’ with area outputs driven by pupil numbers and an associated cost output, both of which gives central government a greater degree of programme certainty. The performance metrics are prescriptive. Daylight, room proportions, air quality, carbon in use and biodiversity net gain requirements, all need due care and attention, and are required to be evidenced in the design solutions to enable central government to consistently measure building performance and the impact of the investment on a local, regional, and national basis.

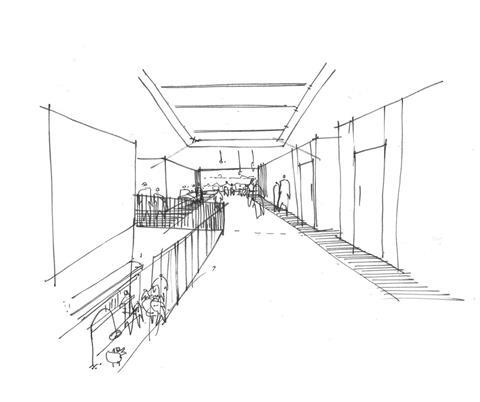

What is not defined is how the components are assembled.

The baseline designs are templates to visualise the opportunity as a starting point to elicit a conversation and to help finalise briefs for school building projects, for discussion with local planning departments and to define the funding envelope. As the skillsets in local authorities have drifted to the centre, in this case the DfE, the baseline design options have for many organisations become the answer and benchmark to the question before it has even been asked. This is an unintended consequence of a standardised approach but understandable, particularly in a volatile market.

Queen Elizabeth High School and Hexham Middle School

Queensferry High School

Sources: © Andrew Heptinstall and © Keith Hunter

Delivery

The delivery of public sector school programmes involves construction teams from the very off. This is practical and, when applied well, can be the right way to derive value, programme certainty and quality assurance. Working with the right contractors in an environment of trust produces successful buildings, complimented by tried and tested approaches, which have a natural tendency to produce consistent outcomes. This is a result of the knowledge of those involved, the upstream preparations of the DfE and an understanding of how to deliver to the prescribed guidance.

The timescales associated with the opportunities are extreme but have been proven to be achievable, it is not however a process for the faint hearted. The design of a £30m secondary school is ostensibly frozen in a six week period, which has recently reduced to three. The offer, including the financial deal, is reviewed over a period of two to three weeks and then the successful partnership is given preferred contractor status and instructed to progress with securing planning approval. Projects are then on site within three or four months.

These are all significant achievements but is there a cost?