Alright, it hasn‚Äôt got the shops, the offices, the hotels or the gleaming infrastructure ‚Äď but then, that‚Äôs precisely why the so-called ‚ÄėBalkan Tiger‚Äô is such a find for UK construction

IIf you‚Äôve ever looked at Transparency International‚Äôs Corruption Perspectives Index, you‚Äôll know that Serbia is not the easiest place in the world to do business. The 2008 Index put it 85th out of 180 countries: it scored 3.4, compared with 9.3 for the cleanest nations (Denmark, Sweden and New Zealand). But Dragan Zupanjevac, the Serbian deputy ambassador to the UK, is adamant this perception is exaggerated: ‚ÄúThere is corruption,‚ÄĚ he says, ‚Äúbut Serbia is a European country, with sophistication.‚ÄĚ Well, he is on a mission to attract British construction companies to his country after all ‚Äď but does he have a point?

Certainly before the global downturn took hold, Serbia looked an appealing market. After 40 years of communism followed by 10 years of war, it had a budding tourism industry and a growing middle class. Last year GDP grew by 8.7%, making it the fastest growing economy in the region.

The so-called ‚ÄúBalkan tiger‚ÄĚ was also ranked as the third most attractive country for foreign direct investment by Pricewaterhouse Coopers.

This growth is not going to be wiped out by the recession, either. The Serbian Central Bank predicts GDP will continue to grow by at least 2% in 2009. This is partly because Serbian banks are more conservative than most and thus eshewed the higher risk investments that have done so much damage in the UK.

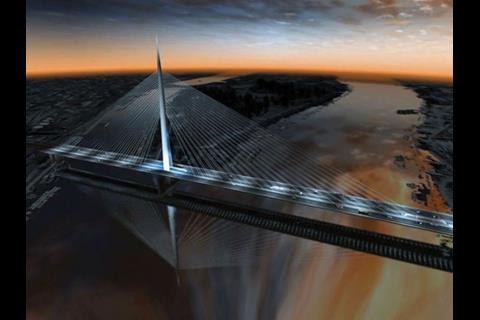

Best of all, its construction industry looks relatively robust. Zupanjevac estimates that more than ‚ā¨7.9bn (¬£6.9bn) will be spent on construction in the next five years. In January, the government announced plans to spend ‚ā¨4bn (¬£3.5bn) on infrastructure over the next four years.

So why are so few UK construction companies already here? Greek, Italian, Austrian and German firms have been steadily ploughing money into the region since the fall of Slobodan Milosevic in 2000, but Brits seem to have been put off by rumours of excessive red tape around planning, the fact that Serbia is not yet an EU member status and its troubled history.

Speak to Brits who are actually working in the country, however, and they will tell you that are ways of avoiding these problems. Simon Hindshaw, Scott Wilson‚Äôs regional director for central and eastern Europe, says it is important to choose your clients carefully. In fact, ideally, you should only do projects backed by the EU. ‚ÄúYou should be wary of just giving money over to local authorities,‚ÄĚ he says.

Hindshaw says Scott Wilson only ever does projects funded by the European Investment Bank, because the assessment of tenders takes place in London or Luxembourg, rather than Serbia. According to Hindshaw, if it‚Äôs done in Serbia, there is a danger that whoever pays the most could win the contract. ‚ÄúThere tends to be a better chance of having a clean tender if it‚Äôs done by a European institution.‚ÄĚ

Johnson believes EC Harris has minimised problems by setting up a local office and employing locals. ‚ÄúIf a UK firm just marched straight in without any local knowledge, there may be some issues,‚ÄĚ he says.

Planning permission, however, remains a big stumbling block. Problems arise because of Serbia‚Äôs communist past. ‚ÄúThere is a big issue surrounding land title,‚ÄĚ says Johnson. ‚ÄúPeople will challenge new office blocks that are built, claiming they owned the land before the communist state took it over. It can be a big problem for developers.‚ÄĚ

Aleksander Djukic, marketing manager at PWC in Serbia, agrees that ‚Äúlaws regulating this field are very complex, and getting a planning can be a long process.‚ÄĚ But new legislation to speed up the process is in the pipeline. And while that‚Äôs coming through, ‚Äúone-stop‚ÄĚ consultancies are being established to help get paper work done in one place.

Serbia‚Äôs lack of EU membership has also kept UK firms away in the past. But now, due to its position as a pre-accession country, funding from EU programmes is coming through, including a European Investment Bank loan in December 2008 of ‚ā¨120m (¬£105m) to build healthcare infrastructure.

Zupanjevac is optimistic Serbia will be granted EU membership by 2015. But he says that UK construction companies need not wait for that. Serbia’s infrastructure is distinctly tired and the government is keen to attract foreign firms to help improve road and rail. Government clients dominate this sector but PPP frameworks are being talked about, and could be in place by 2010.

Meanwhile, the growing tourist industry is fuelling the need for hotel and shopping malls. Johnson says: ‚ÄúSerbia has skiing in the winter, is famous for it‚Äôs local spas, and is crying out for more hotels to be built. Next door, Macedonia has a lot to offer, and Montenegro is scheduled to be the next Montecarlo. There‚Äôs Serbia, with it‚Äôs great transport links, right at the heart of it all.‚ÄĚ

Johnson says construction opportunities are in ‚Äúpockets‚ÄĚ along Corridor 10, a highway that stretches from Turkey to Austria. One project raising excitement is the ‚ā¨700m (¬£610m) Fiat factory in Kragujevac, which is currently inviting tenders.

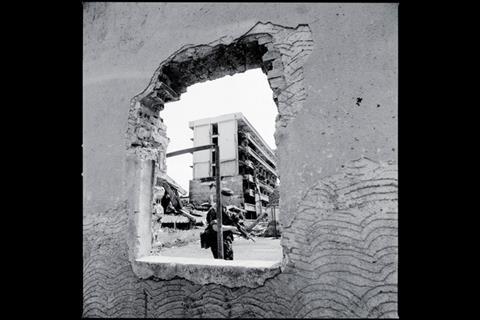

The other hotspot is the rapidly expanding capital. Two million of Serbia‚Äôs eight million population live there. There is ‚Äúconstant pressure on the market for newly built apartments,‚ÄĚ according to Djukic, as the emerging nouveau riche demand ‚Äúsexy homes‚ÄĚ to replace the apartments left over from the communist era.

The capital is divided into New and Old Belgrade. The creation of the new city on unclaimed land means most construction in this area can go ahead without the fear of previous owners coming forward. The land is undeveloped, unlike in the old town where people often come forward and claim ownership of land and buildings from pre-Communist times. ‚ÄúIt‚Äôs much easier in the new town,‚ÄĚ says Zupanjevac, ‚Äúand buildings are shooting up there. It‚Äôs becoming Serbia‚Äôs Canary Wharf.‚ÄĚ

A final element that makes Serbia worth a look is that the government is offering tax incentives for foreign companies. These include a 10-year corporate profit tax holidays for large investments.

Although Johnson concedes that ‚Äúthe Serbian economy is not what it used to be‚ÄĚ, it‚Äôs faring a lot better than most of the rest of the world. ‚ÄúSerbia is the silver lining. Its infrastructure needs working on, and there‚Äôs lots of scope for building factories, flats and offices. It‚Äôs our little gem in eastern Europe.‚ÄĚ

Postscript

Original print headline: Is this Serbia’s answer to Canary Wharf?

2 Readers' comments