Ciara Walker, Birgit Detig and Ramiro Forné of Arcadis and CallisonRTKL consider whether Berlin will still be sexy, when it is no longer so poor

01 / Introduction

Berlin has for a long time relied on its image of counterculture, creativity and cheapness to draw innovative start-ups and entrepreneurial people to it, as well as the fact that it is Germany’s cultural centre and seat of government. Now that this tactic has truly paid off, and the beginnings of an economic and real estate boom are visible in the city, the question arises of how Berlin can keep the essential qualities that make it unique while it modernises and gentrifies, consequently becoming more expensive, drawing fewer creatives and start-ups.

A polycentric city known for its diversity of neighbourhoods, Berlin will need to invest in its communities and provide housing across income levels to keep its character while growing into its full potential as a capital city.

02 / Economic and political overview

Economics

From a debtor state recuperating from its Cold War division and reunification, Berlin has finally turned around its economy, growing at 3% in 2016, above the 1.9% average for Germany and consistently outperforming national growth over the past three years.

Berliners have seen unemployment fall from 19% in 2005 to 9.5% in 2016, and much needed growth in real wages. This was accompanied by buoyant urban construction, surging tourism and unprecedented interest in real estate between 2010 and 2015. The city was described in the 1990s as “poor but sexy”, and still needs many years of growing faster than the rest of Germany to catch up.

Berlin is unusual in Germany for having a focus on services over industry. The city is renowned for science and research, with 170,000 students and researchers at four internationally renowned universities, 41 higher education institutions and 67 research centres. Now, with Germany’s Industrie 4.0 policy of investment in the future of industry, Berlin is leveraging these resources to re-industrialise, focusing on high tech and clean tech.

The city’s population is expanding rapidly, with 40,000 added a year as well as the refugees welcomed in 2015 and 2016. This has contributed to economic growth, filling new jobs as they are created, and creating demand for additional goods and services. However, the population growth also presents challenges, requiring additional housing, social infrastructure, infrastructure improvements and even commercial space to accommodate the new jobs being created.

A main challenge for the city is retaining its character while accommodating this additional demand, and the rising prices which will come with booming real estate. Already 600 artist studios have disappeared in the past two years, and initiatives such as the Alliance of Berlin Studio �ǿմ�ýs (conversion of 38,750m2 of former government facility into a housing complex for refugees and creatives) may not be enough to keep Berlin’s counterculture and creative character intact.

Politics

Germany consists of 16 federal states, with income distributed by central government according to the solidarity principle of richer regions compensating poorer. As recently as 2012, Berlin was the biggest recipient, claiming a payment of £2.7bn, due to its East Germany economic legacy and the cost of reunification, but in the last few years it has been paying down its debt with budget surpluses each year. The Berlin Senate has 160 elected members and elects the mayor of Berlin and the eight senators responsible for running the city. The city is further subdivided into 12 boroughs, each governed by a borough council with responsibilities for planning, among other things.

The elections in September 2016 led to a change in local government: the SPD, Die Linke and Die Grünen coalition now jointly govern Berlin. The government is beginning to outline the path forward, and the markets eagerly await the direction taken on important decisions such as whether to allow high rises, or build into Berlin’s green spaces, both unpopular options. They will follow the framework laid out in the Berlin Strategy 2030, which provided an inter-agency framework for long-term sustainable development of the city for the first time since reunification in the 1990s, led by Berlin’s Urban Development Department.

Table 1: City indicators

| City-region indicators (2016) | Berlin | Greater London |

|---|---|---|

| Arcadis Sustainable Cities Index 2016 | 25th | 5th |

| GVA (£) | 89.7bn (2014) | 378.4bn (2015) |

| GVA per head (£) | 26,778 (2013) | 43,629 (2015) |

| Year-on-year economic growth (%) (2015) | 2.20% | 3.20% |

| Unemployment rate (%) (2016) | 9.20% | 6.10% |

| Population (2016) | 3.8m | 8.7m |

| Population growth rate (annual %) (2016) | 1.30% | 5.70% |

| Population density (people per km2, 2016) | 4,049 | 5,518 |

| Overnight stays (2014) | 28.7m | 28.8m |

| CO2 emissions (2011) | 19.8m tonnes | NA |

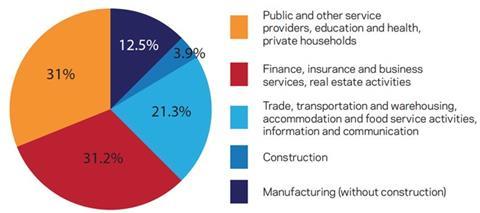

Diagram 1: Gross value added in Berlin 2014

03 / Innovation

The Berlin Strategy mentioned in section 2 acknowledges and highlights the importance of innovation and technology to the Berlin economy. It has identified five innovation clusters to be developed:

- Energy management

- Healthcare industry

- IT, communication, media and creative industries

- Optics

- Transport, mobility and logistics.

Every third company in Berlin is active in one of these clusters, together generating over £87.6bn in revenue, almost 40% of the capital’s turnover. The city is recognised as one of the prime locations for science in Germany, and is among the top three innovation areas in the EU. Some 3% of the workforce work in R&D, and 4.2% of GDP is spent on it, more than any other German state. The Berlin Strategy aims to strengthen this position with investment in facilitating innovation, through improved networks of learning institutions and research centres, development of multiple innovation hubs, safeguarding and developing industrial and commercial space and promoting start-ups with improved access to services, contacts, capital and space. Science parks such as Adlershof