Imagine all members of a project team working from the same building data model⦠Christoph Morbitzer of HLM Architects explains how buildingSMART, the international system of interoperability, is making this a reality

A successful building isnât created by visionary design or inspired engineering, seamless services or masterly project management. Itâs a product of all of those things. Yet the way the construction industry functions throws up so many barriers to effective collaboration.

Until now. We are set for a revolution in the way we work, sparked by an international industry initiative called buildingSMART which enables interoperability between all the different teams working on a project.

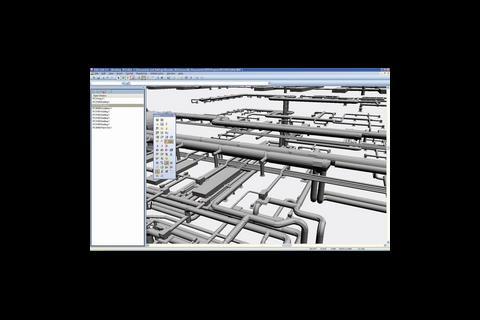

Consultants such as building services engineers and architects will no longer design in isolation from each other, but will be working from the same project database, even though they may be using different software applications.

ÐÇ¿Õ´«Ã½SMART was formerly known as IAI, the International Alliance for Interoperability. This was set up in 1995 and today the initiative involves more than 550 members in more than 30 countries. They include software developers such as Autodesk, Bentley and Oracle; professional practices including HLM Architects, HOK, BDP, Anshen and Allen; contractors including Costain, Taylor Woodrow and Hochtief; and major government organisations in the US, Europe and Asia.

The name change to buildingSMART signifies the fact that the model has now sufficiently matured to be applied in the real world. Indeed, it can be seen as a more sophisticated data model than the ones used in the car or ship building industry â sectors which often set the pace in advanced working methods.

ÐÇ¿Õ´«Ã½SMART enables interoperability by connecting and enabling data exchange between different software applications. It is based on an internationally agreed and accepted open standard called Industry Foundation Classes (IFC). These define how information is expressed and can be used with any type of software.

IFC works by defining âobjectsâ. In the case of a door, for instance, this will include not only the door and its dimensions, but its material, type of finish and fire protection information. It also knows how objects relate to each other, for example where a door is placed in a wall.

Revolution in design

A single data model will revolutionise the way that buildings are designed. Imagine that when you decide to use a certain type of window: once the IAI data model knows the location of the window in the building it can automatically check the cost, thermal properties, structural implications, fire rating requirement, or any other building control issues.

Currently, the data model supports building and planning regulations in Norway and Singapore. In Singapore, it is possible to submit an electronic version of a building project through an internet-based system and receive an automated investigation of its compliance with the building regulations. In the US, the General Services Administration, the body responsible for all federally-funded buildings, requires IFC-based building information models.

More knowledge capabilities will emerge too. Already, the Norwegian building industry's knowledge base from the national research organisation SINTEF is being redeveloped to become available directly to buildingSMART applications.

The construction industry desperately needs more collaboration and this system enables just that. Shape, schedules, cost, client brief and requirements, design and analysis information, procurement and construction data, and operation and manual records ordinarily exist in a single data model to be accessed when necessary. This ensures the project team stays on track and saves valuable time often wasted searching for the most up-to-date documents.

From an operational point of view, the use of information gathered during construction can also be used and updated during the buildingâs lifecycle. And the building owner can use exactly the same project database as that of the building designers, ensuring its accuracy.

Although many of the benefits of buildingSMART described above are holistic, the system has now evolved to accommodate the very specific needs of different professionals within the construction industry. The IFC data model is vast and deals with all information in a construction project from all disciplines at all points in the lifecycle. However, most software applications tend to be more specific. They deal with one application for one purpose at one (or possibly a few) points in the project lifecycle â and this is actually also what the construction professional does. This has so far been a major barrier in the uptake of buildingSMART by the construction industry, but has now been addressed with the introduction of the Information Delivery Manual (IDM), conceived by Jeffrey Wix from AEC3.

IDMs pinpoint the piece of the IFC model that is relevant for the support of a particular task. This is called an âexchange requirementâ and will state the procedure for performing a certain business process (for example, to carry out an energy simulation analysis). It will describe actions that need to be performed; aims to identify most suitable agents to perform the actions; inputs information that enables a process to happen; and outputs information produced during the process.

An exchange requirement is the user-facing part of IDM and describes information in non-technical detail. For the software provider, a "functional part" is provided, which describes the use of every entity, every attribute, every property set and every property required in the process.

Crucially, IDM also delivers flexibility. It is often the case that the information needed in a business process differs slightly from place to place (for instance, determining quantities in a construction project is done differently in the UK and Germany). IDM handles the different interpretation by providing a âbusiness rulesâ component, a set of rules that can be applied to an exchange requirement to âconfigureâ the information output.

Finally, the accuracy of data on which design aspects are based is critical. IDM enables an exchange requirement to be automatically verified by adding business rules that require certain data elements and value ranges for a defined object. Interestingly, the principle is exactly the same for checking compliance with building regulations. It is a simple comparison of the information needed and that provided.

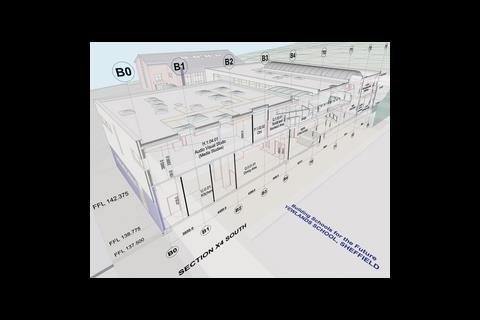

The above description gives a glimpse of a new design world, which will have fundamental implications for the way we work. For a start, we will have to design in 3D, which is still uncommon in the construction industry. The 2D drawings, still standard output using CAD tools, are, in essence, an electronic version of what we used to deliver using a drawing board.

Changes ahead

To facilitate all the benefits I have outlined, this situation will have to change. The effect on work practice will need to be addressed by amended fee arrangements: the engineer will not need to reproduce an architectâs design in 3D in order to carry out an energy analysis using a simulation tool, but the architect may need to spend a bit more time on the creation of an accurate 3D model at the outset. Then there is the requirement of a central server where all the design information is stored, along with data security, confidentiality and data protection issues.

However, all these perceived barriers of buildingSMART can be overcome quite simply, especially if the industry accepts change. Countries such as Norway or Singapore, where buildingSMART and IDM have started to transform the construction industry, are leading the way. A common pattern is that it is so far mainly used by large companies on large projects â which is precisely how the CAD revolution began. I expect that, in a few years, it will have been embraced by companies of all sizes, making it a commonplace tool for all disciplines.

Source

ÐÇ¿Õ´«Ã½ Sustainable Design

Postscript

Dr Christoph Morbitzer is an associate at HLM Architects

No comments yet