The IBM �ǿմ�ý was a cut-down version of architect Denys Lasdun’s plans for a complementary neighbour to the National Theatre on the banks of the Thames. AHMM’s recent refurbishment, which sees the building brought firmly into the 21st century, means that original vision is now complete

Slowly but surely, the public realm on the east side of the National Theatre has got better over the years. A once dismal service road, Stage Door Avenue, between Upper Ground and the riverside path, was improved in 2015 by banishing the theatre’s service yard at the end by the Thames. The former service yard is now a bustling restaurant area and the lorries making deliveries to the theatre and collecting rubbish have largely gone.

But the shine was dulled by the IBM building across the road from the theatre. A high brick wall and brick plinth that shouts “keep out” runs the length of Stage Door Avenue.

The building corner at the Waterloo station end of Stage Door Avenue is sullied by two car ramps; one behind the high wall up to the entrance and the other down to a subterranean car park. Office workers are banished to a pedestrian ramp between the two dedicated for cars, with protection provided by a cheap bus shelter-type canopy.

“The entrance, by any modern standards, would be deemed to be deflating,” says Simon Allford, executive director and head of studio at architect Allford Hall Monaghan Morris who was responsible for the building’s recent refurbishment. “For a building of this scale and intensity of use, there’s no sense of scale, generosity, arrival or indeed clarity of where you’re going in the building from here. By our modern standards of legibility and light, you are just heading towards a hole in the wall.”

AHMM’s refurbishment with contractor Multiplex has given the quality of the public realm here an enormous boost and made it a much better place to work. The forbidding brick wall and vehicle ramps have been swept away and replaced by low steps leading up to a colonnade with generous glazing behind that protects an enormous double-height reception area.

The ugly car ramps have gone and have been replaced by a new entrance dedicated to people, not cars. These changes are the most visible manifestation of this refurbishment that has seen the building, which was completed in 1983, stripped back to its frame and remodelled to make it fit for 21st-century office occupiers.

Inside, the reception area is vast – it takes up 10,000ft2 of the building. The concrete frame of this Denys Lasdun-designed brutalist building is left exposed with the ghost of the former main entrance ramp expressed by the stumps of the former ramp supporting beams, which have been sawn off where these met the columns.

In a nod to the Barbican Centre – another brutalist building of the same era – the flooring is formed from blocks of larch orientated on their ends. This, combined with finely slatted, strategically placed wall and ceiling panelling, brings a touch of warmth to the interior.

This is flooded with light from the glazing running the length of the reception and entrance area. Bespoke light fittings designed to match the period add a dash of style too.

The reception opens out halfway along where the cars dropping off visitors by the former main entrance once turned around. A huge concrete transfer beam supports the floors above and, behind the security barrier line, there is an obviously contemporary insertion in the form of a steel stair which extends the full height of the building and offers workers views over the reception as they circulate between floors.

The stair treads are formed from bespoke chunky granite aggregate terrazzo tiles, with the balustrade sides lined with timber slats and lit by concealed LED strips making it feel more like a smart, modern hotel than an office. The stairs open out to the lift lobby on each floor and these feature the same flooring as the reception with the lift shaft wall formed from cast glass.

Allford says these are the most obviously accessible stairs that the practice has already done and, every time he visits, the building people are using these rather than the lifts.

The office floors feel contemporary as these are 2.9m high from the raised access floor to the lowest point in the ceiling mounted services. Air distribution is at a high level with heating and cooling provided by fancoil units.

Allford says that the carefully choreographed, minimal service layout should make it easier for office occupiers to configure their space without resorting to wasteful bespoke fitouts which get changed every few years.

And each floor benefits from full-length external terracing surrounding the building so that a worker could walk from the terrace on the west side, through the office floor and out again to a terrace on the east. The terraces are attractively planted for workers to enjoy and the building position next to the Thames offers great views over London.

The building’s history

In many ways the terraces are an anomaly as the building dates from a time when access to outside space for office workers was not a consideration. The principal reason why the IBM office has such generous terraces is because it was designed as a sister building to the National Theatre, which is distinguished by its strongly linear, stepped terracing representative of the strata in rock.

Denys Lasdun was commissioned by the government in 1963 to design a theatre and an opera house next door on the South Bank near the Shell Centre. He designed the buildings as a pair with both featuring wide, stepped terracing, which was a feature of Lasdun’s work, and distinctive fly towers.

The opera house was scrapped with the National Theatre going ahead on a new site 500m down river. The theatre had a troubled birth, taking 13 years to build and was finally opened in 1976.

When IBM approached Lasdun to build a marketing centre next door to the National Theatre in 1977, he revived the notion of a complementary building pairing, which is why the IBM features similar, generous stepped terracing to the National Theatre and a facsimile flytower in the form of an extended core. Like the theatre it featured external columns, although the latter features distinctive angled columns supporting the lower terrace which are said to reference the cranes found on the former dockside.

A subtle difference between the buildings was Lasdun’s treatment of the exterior concrete finish; the National Theatre featured boardmarked concrete whereas the exterior texture on the IBM building is provided by granite chippings carefully laid into concrete.

At the time the south side of the river was dominated by maritime industry, so pedestrian access was limited. Riverside access was extended as far as the National Theatre and the IBM end building where it finished. This explains why the National Theatre’s service yard was on the river side of the building.

By the time the IBM building was completed in 1983, architectural design had moved on. Brutalism had given way to post modernism and high tech and the 1960s trend of designing buildings around the car rather than pedestrians was on the way out.

Internally, the design was typical for the period. The office areas featured suspended ceilings concealing the services with much of the space given over to cellular offices with open-plan area desks separated by partitions. The generous external terracing was not readily accessible and covered with inhospitable ballast.

This was the how the interior was configured when AHMM won the competition to revitalise the building in 2019. “The terraces, which Lasdun took from the idea of the public spilling out from the National Theatre to enjoy a gin and tonic, were used for maintenance,” Alford says.

The windows were single glazed, the building badly insulated and heated and cooled by fossil fuels. The building was also smaller than the potential offered by the site.

“It wasn’t based on maximising the opportunity but on what IBM actually wanted,” Allford says. They wanted 200,000ft2 net – and that’s what Lasdun built for them.”

The changes

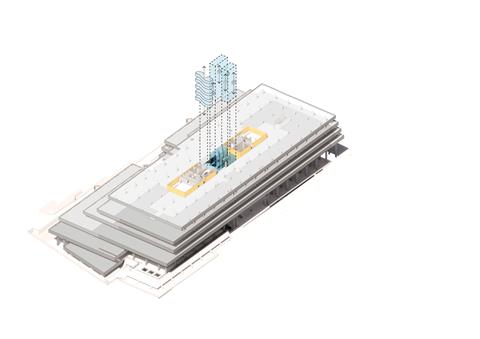

The floor area needed to be significantly extended to meet the cost of bringing the building up to modern standards. AHMM applied for planning to add two floors to the building and extend it by up to 16.8m to the east and 3.4m to the south. The 20th Century Society objected to what it called “heavy-handed” proposals and applied for a grade II listing, which was granted.

AHMM went back to the drawing board and cut the number of additional floors to one and scrapped plans for making the sunken area on the side of the river more accessible by slicing off a section of the balcony in this area at ground-floor level to create space for a pedestrian ramp.

We’re pretty consistent with the idea that Lasdun had before IBM’s brief retreated

Simon Allford, executive director and head of studio, Allford Hall Monaghan Morris

AHMM’s revised proposals were boosted by the discovery of drawings showing that Lasdun originally designed a bigger building as this would have better matched the original composition of opera house next to a theatre. “The 20th Century Society was very concerned about this extra floor, but we found this [drawing] in the archives and could say [to the 20th Century Society] that you keep saying this is what Lasdun wanted, but what he wanted was a composition that worked for the National Theatre,” Allford says.

“So, we’re pretty consistent with the idea that Lasdun had before IBM’s brief retreated.”

Construction work was done by Multiplex, who have retained 80% of the original structure and improved the building’s sustainability credentials further by using reclaimed steel for the lift core, contributing to the building’s BREEAM Outstanding rating and upfront embodied carbon of 365kgCO2e/m2. The two lightwells in the centre of the building have been filled in to create more space and a new core between these built for the lifts and stairs.

This intervention, combined with the additional floor and roof extensions, has added 50% more floor space. Some columns were strengthened and enlarged to take the weight of the additional floor.

The building now features modern glazing and heat pumps for heating and cooling helping it to achieve a NABERS design for performance 5* rating.

Allford says a major discussion point during the design stage was the style of the additional floor. He says that as the terraces were conceived as a series of strata, introducing a radically different material would have been wrong.

Instead the extensions have been treated in exactly the same way as the original and are barely noticeable. Indeed, the panels were even made by the same man who made the originals back in the early 1980s.

A search of the archives revealed the name of the company that had made the original panels and the man who was responsible for placing the granite chips in the wet concrete was still working there – so did the same for the new panels. These are slightly paler than the originals, which have been cleaned. Only a keen observer would spot the difference.

This approach to extending buildings dating from the second half of the 20th century is not confined to 76 Upper Ground; two new floors were recently added to the Seifert-designed Space House on the north side of the river using facsimiles of the original structural cladding panels.

There were other changes that Allford would have liked to have made, but couldn’t because of the listing. The height of the windows, which correspond with the line of the suspended ceilings, could have been extended up to the soffit to get more light into the office floors and make better use of the views over the river. This would have meant raising the height of the external panels, and eliminated the need for a white handrail on top of the panels, which Allford dislikes.

“I don’t think the balustrades are an inherent part of the design of the building from within or without,” he says, noting the balcony fronts on the National Theatre are positioned higher relative to the soffit as this building never had suspended ceilings.

It is unfortunate that the listing ruled out changes to the sunken area next to the Thames Path. At a time when the path was a dead end, the priority was keeping people out so there was no access to the sunken area from the path.

Times have changed, with the path now thronged by people, so the sunken area would have been perfect for a public restaurant or café. But creating ramps down to this area would have required partial demolition of the overhanging terrace.

Despite these minor wrinkles, the refurbishment has brought the building firmly into the 21st century and is another great example of how buildings from this era can be reinvented for the modern age rather than being demolished. AHMM’s job was made easier as Lasdun was ahead of his time when it came to providing external space – it is rare for a building of this age, or even one built today to feature such generous terracing, which is now considered so beneficial.

The extra height gained from the new floor suits the building’s proportions better than the original, which looked truncated by comparison. The building is more accessible, with the defensive walls and car-dominated elements stripped away and the building’s vintage has been celebrated by touches such as the end grain flooring, making it more characterful than many new-build offices.

And the exposed concrete gives it a contemporary flavour, too. Taken together, it is another positive step forward for the regeneration of London’s South Bank.

Project team

Client Wolfe Commercial Properties (Southbank)

Development Manager Stanhope

Architect Allford Hall Monaghan Morris

Structural & civil Engineer Heyne Tillett Steel

M&E / sustainability engineer Watkins Payne

Cost Consultant Exigere

Project manager Third London Wall

Planning consultant CBRE

Heritage consultant Townscape Consultancy

Landscape architect Vogt

Lighting design Speirs Major

Main Contractor Multiplex

1 Readers' comment